১০ ফাল্গুন ১৪৩২

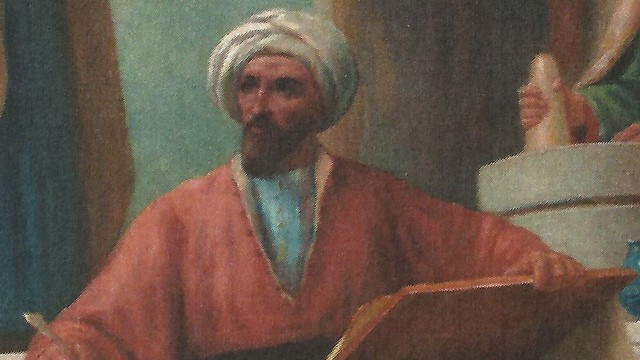

The Legacy of Ibn Sina: From a Young Prodigy to the Father of Modern Medicine

06 November 2025 19:11 PM

NEWS DESK

Bukhara, 980 AD – In the tenth century, this vibrant city was not only a bustling trade center but also a beacon of knowledge and culture. Among the great intellectuals it produced was Abu Ali al-Husayn ibn Abdullah ibn Sina, known in the West as Ibn Sina (Avicenna).

By the age of ten, Ibn Sina had already memorized the entire Qur'an, and his curiosity was as deep as the ocean, never content with trivial matters. While his friends spent time playing marble games, young Husayn (as he was known in his early years) would immerse himself in complex texts. His private tutor, Al-Natili, once sighed and said, “Oh Husayn, I am no longer your teacher. You are a flowing river, rushing forward, and I am just floating in your current. What I had in my mind, you have absorbed before even reaching sixteen.” This acknowledgment marked the beginning of his solitary intellectual journey.

Ibn Sina mastered various fields, from mathematics and geometry to theology and philosophy. But one challenge remained – Aristotle’s Metaphysics. “I read it forty times, stayed awake for forty nights, yet I could not understand. My mind felt like a foggy valley where the sun of logic cannot shine. Is this the end of knowledge?” This was the inner struggle of a brilliant mind.

Whenever faced with a difficult problem, he would retreat to the quiet corners of the mosque, offering non-obligatory prayers, seeking divine guidance for knowledge and clarity. Eventually, it was a commentary by Al-Farabi that unraveled the mysteries of metaphysics for him, leading to a profound moment of enlightenment. Overjoyed, he generously gave money to the poor, reflecting the rare combination of intellect and faith that characterized his character.

At just sixteen, when most of his peers were still uncertain about their paths in life, Ibn Sina had already mastered the theories and practical applications of medicine. He realized that the human body was his ultimate field of study.

When Ibn Sina was seventeen, a life-changing event occurred. Amir Nuh ibn Mansur, the ruler of the Samanid Empire, fell gravely ill. The chief physician of the court, Badruddin, a man of age and experience, failed to diagnose the illness. The hope of the kingdom seemed to fade.

At the request of the Amir, Ibn Sina entered the royal palace. The grandeur of the palace, dazzling to most, did not distract the young scholar. His focus was entirely on the sick ruler.

The chief physician, Badruddin, scoffed at Ibn Sina, saying, “Oh boy, do you think you know more than us? Can you even feel the patient’s pulse?”

With calm yet firm confidence, Ibn Sina replied, “Sir, I may be young, but knowledge does not depend on age. The pulse does not only indicate the flow of blood—it can reveal the hidden truths of the soul.” He gently held the Amir’s hand, closed his eyes, and after a long moment of listening to the pulse, he proclaimed, “The Amir is not physically ill—he is lovesick.”

This revelation shocked the court. Ibn Sina explained that the Amir’s physical weakness was the result of deep emotional pain, a psychosomatic condition. His pulse was irregular, but not due to any physical illness—rather, it was a sign of profound emotional trauma.

To confirm his diagnosis, Ibn Sina had a servant recite names of streets and neighborhoods in Bukhara. When the name of a specific street and a particular young woman’s name were mentioned, the Amir’s pulse raced wildly, and a flush appeared on his pale face. Ibn Sina concluded that the Amir was suffering from unrequited love, and the cure lay in reuniting him with his beloved.

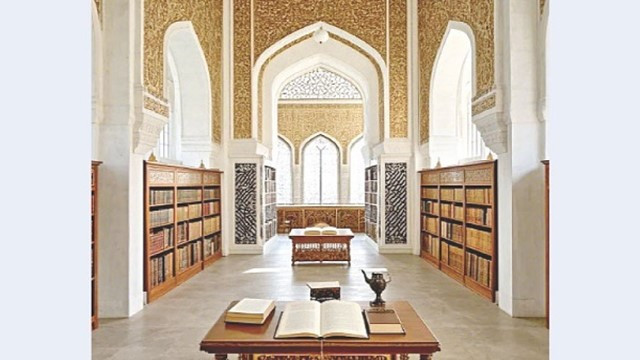

When the Amir’s health began to improve after this advice, he called Ibn Sina to thank him. In gratitude, the Amir offered him gold, jewels, and the highest office of the state. But Ibn Sina, with humility, declined the wealth and power, saying, “My Lord, I seek nothing but the opportunity to enter your royal library. For it is knowledge I desire, not riches.”

The Amir, moved by his response, granted Ibn Sina unrestricted access to the royal library—a treasure trove of ancient texts. It was here that Ibn Sina immersed himself in Greek, Egyptian, Indian, and Persian works, further enriching his knowledge. This library became the foundation of his future accomplishments.

Around 1001 AD, Ibn Sina’s father passed away, and soon after, Amir Nuh ibn Mansur also died. Political instability swept through Central Asia. Realizing that Bukhara was no longer a safe place for intellectual pursuit, Ibn Sina embarked on a journey that marked a new chapter in his life. His travels took him to Khwarazm, a prominent center of learning at the time, where he met the legendary scholar Al-Biruni. The two engaged in profound discussions on science and philosophy, leaving a lasting mark on the history of knowledge.

Eventually, after many travels and political challenges, Ibn Sina settled in Hamadan, Persia. When the ruler Shams-ud-Dawla fell ill, Ibn Sina successfully treated him. Grateful for his recovery, the ruler appointed Ibn Sina as the prime minister. During the day, he navigated the complexities of politics and warfare; at night, by the light of a candle, he wrote.

This dual life of politics and academia took a toll on Ibn Sina, but his thirst for knowledge never wavered. It was in Hamadan that he began writing his most famous works, including Kitab al-Shifa (The Book of Healing), where he introduced psychology as an integral part of medicine. He also completed his groundbreaking work, Al-Qanun fi al-Tibb (The Canon of Medicine), which became the standard medical textbook in Europe for over six centuries.

Ibn Sina's life was a continuous journey of learning and teaching. Over the course of his career, he authored more than 450 works. He was not only a physician but also an astronomer, mathematician, philosopher, and poet. He was the first to recognize tuberculosis as a contagious disease and provided detailed descriptions of meningitis.

Ibn Sina passed away in 1037 AD, at the age of 58, in Hamadan. The young boy from Bukhara, who chose the doors of a library over wealth and fame, became known as “Ash-Shaykh al-Ra'is” (The Chief of the Thinkers) and the "Father of Modern Medicine." His work Al-Qanun fi al-Tibb remained a core textbook in European universities for over 600 years. Ibn Sina proved that while individuals are mortal, knowledge is eternal.

Comments Here: