১০ ফাল্গুন ১৪৩২

Research Reveals Story of The 'Lost Century' of Arabic Literature

08 November 2025 19:11 PM

NEWS DESK

Arabic literature is still partly shaped by a story written in Europe more than a century ago.

It begins in the eighth century, when Baghdad under the Abbasid caliphs became a centre of science, philosophy and poetry – a period regarded as the golden age of Islamic civilisation.

At the heart of that era were poets such as Abu Nuwas and Al Mutanabbi, alongside polymath philosophers Al Farabi and Avicenna, who came to represent the height of an Arabic intellectual culture that illuminated the world.

This framing emerged from 19th century European scholars, including France’s Ernest Renan and the Netherlands’ Reinhart Dozy, who argued that Arabic intellectual life then declined after the 11th century, leading to an 800-year lull before Europe’s Renaissance.

It is a view steeped in Orientalist bias and historical oversimplification, current scholars say, as the Arabic literature never fell silent.

Speaking at a panel organised by the Sheikh Zayed Book Award at the Frankfurt International Book Fair, linguists and literary historians noted that Arabic writing continued to evolve in that it was copied, performed and translated, even when not formally acknowledged.

These reassessments underpin the work of modern researchers such as Germany’s Beatrice Gruendler, German–Turkish scholar Hakan Ozkan and American academic Maurice Pomerantz of NYU Abu Dhabi, who argue that Arabic literature developed unabated.

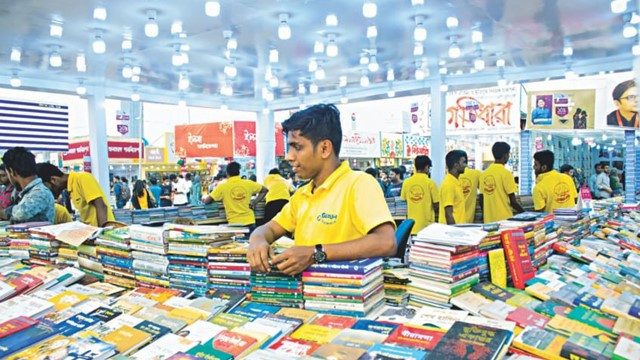

Gruendler describes the idea of a “lost century” in Arabic literature as a myth. Her non-fiction work The Rise of the Arabic Book, recently shortlisted for 2025 Sheikh Zayed Book Award for Arab Culture in Other Languages, recalls the thriving and competitive literature and publishing industry in ninth century Baghdad that echoes in book fairs today.

“You had professional copyists, bookshops and reading public,” she says. “If you walked through Baghdad, you would have seen scribes taking commissions, arguing over punctuation, advertising their handwriting. It was noisy, competitive and entirely familiar.”

That fact alone, she says, challenges the idea that formal publishing began in the 15th century in Germany with the arrival of Johannes Gutenberg’s printing press.

A reason behind the Western narrative about Arabic literature, she says, lies in the way European Orientalists thought of a civilisation's trajectory.

“They wanted Arab history to look like theirs, with a beginning, a peak and a fall,” she says. “But Arabic literature doesn’t fit that pattern. It never stopped moving.

“The centres changed from Baghdad to Cairo to Damascus to Andalusia, but the conversation continued. The same poems were copied and reinterpreted, new genres appeared and older ones were reshaped. The language adapted to every place it went.”

That continuity can also be traced through poetry. Ozkan, professor of Arabic literature at France’s Aix–Marseille University, explores the topic in his study The History of the Eastern Zajal: Dialectal Arabic Strophic Verse from the East of the Arab World, shortlisted this year for the Sheikh Zayed Book Award in the category of Arabic Language and Literature.

The research shows how zajal, a rhythmic, dialect–based form of poetry long dismissed by both European and Arab academics as uncouth, continued to evolve long after the Abbasid period.

“These poets broke rules because they could,” he says. “They mixed registers, played with rhyme, mocked scholars and praised saints. Some of it reads like early rap. It’s the sound of a culture that’s alive.”

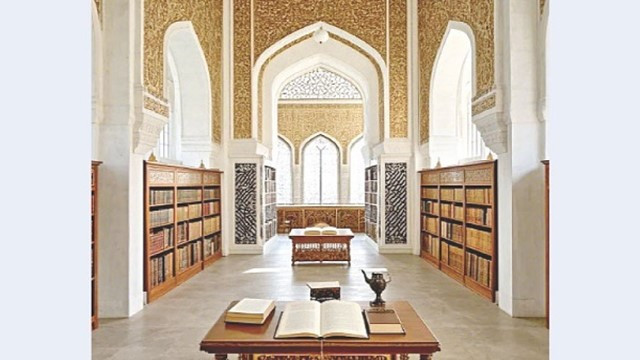

Further restoration is also happening at New York University Abu Dhabi with its Library of Arabic Literature, a series that helps bring back works from the supposedly lost centuries after the Abbasid period. Published in Arabic and English, it has already produced more than 60 volumes of prose, poetry and philosophy since its launch in 2010.

“Editing these books is like joining a conversation that never stopped,” said Maurice Pomerantz, one of the series editors and a professor of literature at NYU Abu Dhabi. “You can see generations of writers answering one another, authors, commentators, translators, all adding layers. The manuscripts are alive with argument.”

As for why the idea of Arabic literature’s decline took shape over the years, Pomerantz says it has less to do with history than with access. “If a text isn’t translated, it doesn’t exist globally,” he says.

“That’s why awards and institutions matter. The Sheikh Zayed Book Award, for example, recognises scholarship about Arabic culture written in any language. It brings visibility to research that might otherwise stay inside the academy.”

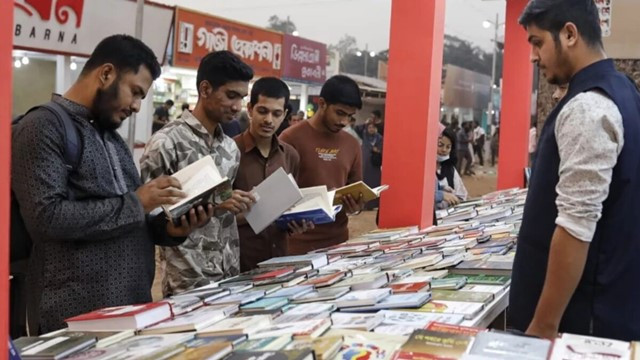

He adds that the real challenge now is ensuring these works live beyond academic circles. “We need to make them part of the public imagination again, taught in schools, read in translation, performed on stage. Otherwise the myth will just grow back.”

Comments Here: