The controversy cuts both ways — politically, over who has the authority to issue such an order, and legally, over whether the move is permissible under the existing constitutional framework.

Although most political parties agree in principle on holding a referendum on the July Charter, they remain divided over its timing and method.

The Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) has denounced the commission for removing parties’ notes of dissent from the draft, accusing it of “deception” and “betraying consensus.” The party insists that the referendum, if held, should coincide with the upcoming general election and that the elected parliament should oversee the reform process.

The Jamaat-e-Islami, while also seeing its dissent omitted, has expressed continued trust in the commission. It supports holding the referendum before the election, and argues that the chief advisor — not the president — should issue the order, as the current government represents the “popular uprising.”

The National Citizen Party (NCP), meanwhile, has taken a more assertive stance, demanding that the order be proclaimed from the Central Shaheed Minar before polls.

The commission’s draft order claims it will be issued “on the basis of the sovereign authority and intent of the people as expressed through the popular uprising,” despite the constitution having no such provision. It proposes two possible routes:

-

Drafting a full constitutional amendment bill for approval by referendum, or

-

Forming a Constitutional Reform Council, which must complete its work within 270 days — after which, if unfinished, the referendum-approved draft would be automatically inserted into the constitution.

Legal experts have strongly questioned the proposal. Senior lawyer Ahsanul Karim argues that the current process “has no constitutional basis,” saying only parliament can initiate amendments with a two-thirds vote. Former secretary AKM Abdul Awal Majumder insists that only the president can issue a constitutional order, warning that any move by the chief advisor would be symbolic rather than binding.

Former Chittagong University professor Nizamuddin Ahmed criticised the commission for dropping dissenting views, saying it “created division instead of consensus.”

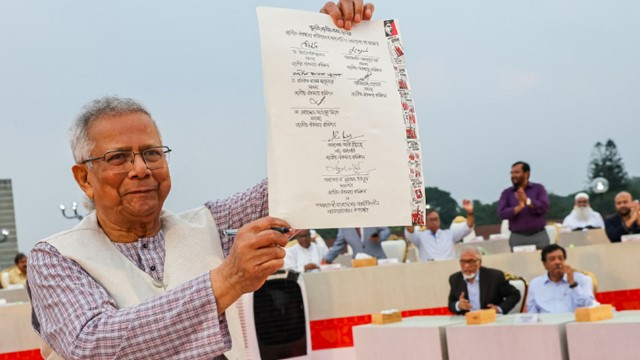

The 2025 July National Charter, signed by major parties at the South Plaza of the parliament building after the July uprising, outlines 84 reform proposals — 48 of which require constitutional amendment. However, more than 100 dissenting notes were recorded during negotiations, most of which were omitted from the final draft.

Analysts say the government now faces a crucial decision: whether to proceed with the commission’s controversial roadmap or seek broader political agreement first. As divisions deepen, the future of the July Charter — and the next phase of Bangladesh’s constitutional journey — hangs in the balance.

Comments Here: