১০ ফাল্গুন ১৪৩২

Nobel Prize 2025

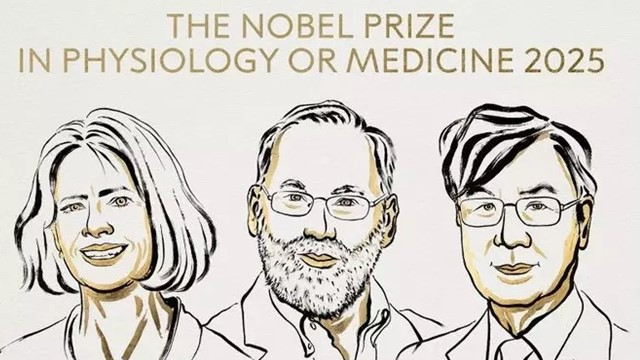

Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine Has Been Awarded to A Trio of Scientists

06 October 2025 17:10 PM

NEWS DESK

The 2025 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine has been awarded to a trio of scientists – two of them American and one Japanese – for discovering how the immune system protects us from thousands of different microbes trying to invade our bodies.

Mary E. Brunkow, Fred Ramsdell and Shimon Sakaguchi will share the prize “for their fundamental discoveries relating to peripheral immune tolerance,” the Nobel Committee announced Monday at a ceremony in Stockholm, Sweden.

The laureates identified “regulatory T cells,” which function like the immune system’s security guards and prevent immune cells from attacking our own body, a cause of autoimmune diseases.

“Their discoveries have been decisive for our understanding of how the immune system functions and why we do not all develop serious autoimmune diseases,” said Olle Kämpe, chair of the Nobel Committee.

The findings have led to the development of potential medical treatments that scientists hope could cure autoimmune diseases, the committee said, as well as providing more effective cancer treatments and reducing complications after stem cell and organ transplants.

The immune system, which the committee called an “evolutionary masterpiece,” protects us from disease first by differentiating pathogens from the body’s own cells, then by attacking these invading microbes. To try to evade the immune system, pathogens develop similarities to human cells as a form of “camouflage.”

If pathogens camouflage themselves successfully, this can lead to a sort of biological “friendly fire,” in which the body’s immune system attacks its own cells, unable to tell the difference between an invading pathogen and what was already there.

The committee said that Sakaguchi, a Japanese immunologist now at Osaka University, made a groundbreaking discovery in 1995 which helped to explain why the immune system does not attack our bodies more frequently.

By examining mice and the role of the thymus – the organ in which T cells mature – Sakaguchi learned that the immune system must have some other form of “security guard” to stop the body from attacking itself. This newly identified class of immune cells were named “regulatory T cells.”

Brunkow and Ramsdell, both American, built on Sakaguchi’s discovery in the early 2000s when they explained why a specific type of mouse was particularly vulnerable to autoimmune diseases. Their experiments took many years. Whereas mapping a mouse’s genome today only takes a few days, “in the 1990s, it was like looking for a needle in a giant haystack,” the committee said.

Eventually, Brunkow and Ramsdell identified a mutation in a particular gene in those mice, which they named Foxp3. They then showed that mutations in the human equivalent of this gene cause IPEX syndrome, a serious autoimmune disease.

In 2003, Sakaguchi linked their findings to his discovery in the 1990s, proving that the Foxp3 gene governs the development of the regulatory T cells.

Thomas Perlmann, secretary of the medicine committee, said he had spoken with Sakaguchi before the announcement, and that he “sounded incredibly grateful.” Due to the time difference between Sweden and the United States, Perlmann said he had not yet been able to contact Brunkow and Ramsdell.

Brunkow is a program manager at the Institute for Systems Biology in Seattle, while Ramsdell is a co-founder of Sonoma Biotherapeutics, a biotechnology firm in San Francisco.

Last year, the prize was awarded to US scientists Victor Ambros and Gary Ruvkun for their work on the discovery of microRNA, a molecule that governs how cells function in the body.

In 2023, the prize was awarded to Katalin Karikó and Drew Weissman, for their work on messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines, a crucial tool in curtailing the spread of Covid-19.

The prize carries a cash award of 11 million Swedish kronor ($1 million).

Comments Here: