১০ ফাল্গুন ১৪৩২

Two Films Reimagine Begum Rokeya : From Dreamscapes to Documentary Truth

09 December 2025 20:12 PM

NEWS DESK

In the long corridors of Bengal’s history, Begum Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain walks like a silent flame—faint in light, eternal in radiance.

Born into an era when women’s lives were confined behind invisible walls of restriction and prohibition, she carved a small door of light for herself—a doorway that became the blueprint for countless women’s futures. Over a century later, Begum Rokeya is not merely a historical figure; she is a pulse, a living consciousness.

Two very different films now attempt to capture that pulse. The Spanish animation El sueño de la sultana (“Sultana’s Dream”) offers a creative reimagining of Rokeya’s iconic 1905 story, while the Bangla documentary Rokeya: Alor Dooti (“Rokeya: Messenger of Light”) seeks the real woman behind the legend. One soars through the wings of imagination; the other returns to the soil of memory. Yet both illuminate the same truth: Rokeya does not belong to any single time, language, or nation. She belongs to all those who dream of justice and equality.

El sueño de la sultana: A Dream Reborn

The story begins on a rainy day, a reminder that great journeys often emerge from paused moments. Spanish filmmaker Isabel Herguera discovered Rokeya’s work while sheltering from rain in an art gallery in India. There, a book cover caught her eye: a woman piloting a strange flying machine, her eyes glowing with rebellion and wonder. That fleeting moment became the inspiration for El sueño de la sultana. The book was none other than Begum Rokeya’s Sultana’s Dream, first published in The Indian Ladies’ Magazine in 1905.

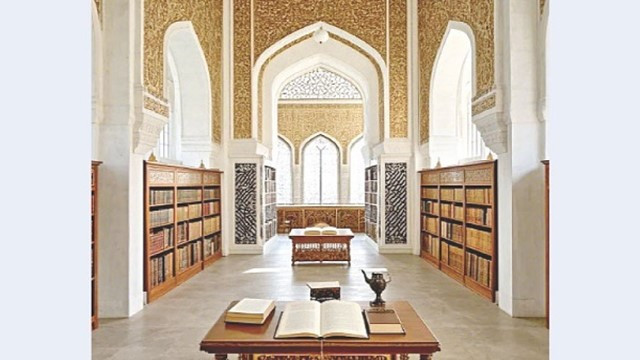

Herguera did not take the simple route of literal translation. Instead, she weaves together three worlds: the journey of a contemporary woman’s quest, the shadowed realities of Rokeya’s life, and the luminous “Ladiland” Rokeya imagined over a century ago. Using watercolors, chiaroscuro, cut-out animation, and layered designs, the film creates a visual language at once ancient and futuristic—just as Rokeya’s writing radiated inner light.

Ladiland is more than imagination; in its 1 hour 26-minute runtime, it evokes a memory of a bygone world. A city emerges from the soft lines of traditional Bengali henna patterns, and women’s laughter floats like melodies cutting through the darkness of the past. At moments, one imagines Rokeya standing behind the animation, watching in astonishment as her dream crosses borders to take on a new form.

Released in 2023, the film is not a literal biography. Instead, it explores the inner world of Rokeya’s imagination. Why did she write what she wrote? How did a woman, confined behind strict societal walls, envision flying machines, solar-powered kitchens, and women-led scientific communities? The film is a meticulous exploration, presenting Rokeya not only as a reformist but as an artist of possibilities.

Rokeya: Alor Dooti – Returning to Memory

If El sueño de la sultana opens a door to dreams, Rokeya: Alor Dooti brings viewers to the courtyard of memory. Its language is measured, its rhythm calm, but its honesty is profound. Here, Rokeya is no symbol—she breathes, struggles, and thinks as a human being.

The documentary traces the young girl who secretly learned Bengali and English, the young woman encouraged by her progressive husband Sakhawat Hossain to write, the widow who built schools for girls despite societal resistance, and the writer who inscribed her name on history through perseverance and determination. Through letters, interviews, and archival photos, the 1-hour film—directed by Mujibur Rahman, scripted and edited by Bappaditya Chattopadhyay, with narration by Debashish Basu and Sutapa Chattopadhyay—renders Rokeya more intimate, more human.

At a time when questions of equality, women’s freedom, and justice remain unresolved, Rokeya’s Ladiland retains its significance—not as a dream but as a guide. Together, these two films illuminate South Asian feminist thought as deeply rooted and historically rich. The fact that a Bengali Muslim woman imagined such a future over a century ago challenges the world to rethink its perspective.

Comments Here: